The Wind So Mild

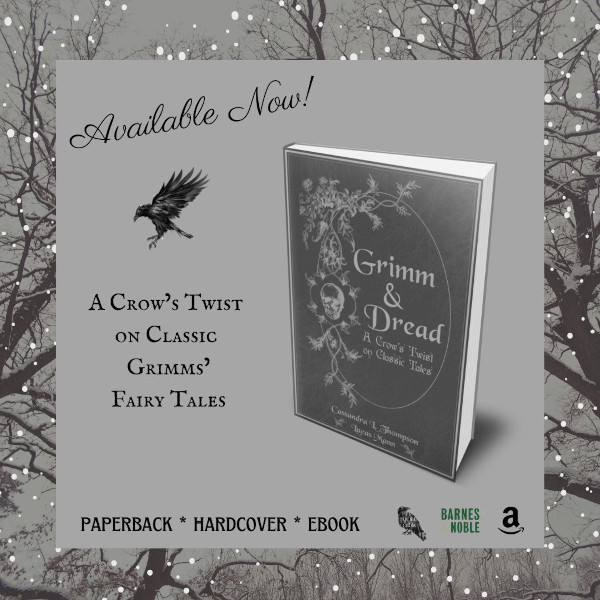

First published in Grimm & Dread by Quill and Crow Publishing House.

"I loved all of them, but I think my favourite out of the bunch is The Wind So Mild, a Hansel & Gretel retelling by Victoria Audley. Such a turn of events where I actually felt sympathy for the witch by the end of it!" - Sophie Brookes, Amazon review

"The various talented authors reignite your love for childhood classics, twisting them into an immersive and gloriously dark experience as masterful and haunting as Carter’s ‘ The Bloody Chamber’." - Melanie Dodd, Amazon review

"There was a little more feminism than I prefer in my stories but that's just a personal preference." - Goodreads review

-

I was born in a time of famine. Dry gusts of wind stung my eyes and rattled the withering bones of the trees. The brittle grass was sharp and brown, and the ground beneath it hard and unyielding. Lack was always with me; we did not have the luxury of thinking about anything except what we did not have. Aching hunger woke me in the morning, and pain felt heavy as a stone on my chest. I did not run and play with other children, not even my siblings. None of us had the energy.

My mother was a witch before me. Magic lived in her touch, and no matter how loud my stomach growled, the soothing stroke of her hand on my forehead calmed my fretfulness long enough for me to fall asleep at night. Later, I would ask her why she did not do more — why she did not raise crops from the dead soil or fatten starving livestock for slaughter. A good witch, as she taught me, understands the limits of her power, but does not fail to act on what is within her power to do. My mother was a powerful witch, but even she could not defy a famine. Still, there were uses for what talents she did have.

One morning, I awoke to an unfamiliar smell drifting in from the kitchen. I rubbed the dust of sleep from my eyes and toddled into the kitchen, still wavering with hunger and early waking. My mother stood over the stove, stirring something in a large pot. Her bare arms were stained a faded crimson to the elbows. I asked her where my father was. “Oh,” she said lightly, “I’m sure he’s around.”

She placed a bowl in front of me at the table, filled with blood red broth and small chunks of pale flesh. I had never eaten so well in my life.

I hardly noticed my father’s absence, now that there was food to occupy my thoughts and time. My siblings and I ate, and we grew. Eventually, of course, the mysterious food store ran out. My mother rationed carefully and made it last as long as she could, but as the stock dwindled, her eye turned on me and my siblings. I felt her sight on us even when she was not in the room, observing and scrutinising. At first, I did not mind, but in time I grew so tired of the constant feeling of being watched, I imagined a wall between her and myself every time I felt her gaze. One night, after a day spent behind the imagined wall, she looked at me in person over the kitchen table, smiling oddly.

I was terrified when she took me aside after we ate, her eyes wild with excitement. But she smiled, and brushed my forehead with her reassuring touch. Taking my hands in hers and squeezing gently, she whispered, “My darling, you have magic in you.”

It was then she told me she was a witch, and that, in time, I could be one, too. She began to teach me what she knew, while watching carefully to see what my special talents would prove to be. On the one hand, she had hoped more than one of her children would inherit her gifts and show an aptitude for magic, but, all things considered, it was convenient that she only had to save one of us.

My sister slept soundly beside me, her breathing shallow and rhythmic. I lay awake, watching the rise and fall of her chest, guessing what she dreamed about: white birds, or colourful gardens, or sweet cakes. The house still smelled of our last meal, and the wind rattled the closed window. The bedroom door slowly creaked open and our mother stepped in, holding a large knife. She held one finger to her lips. I echoed the gesture. The silver blade caught a flash of moonlight as my mother held it high. My sister’s eyes did not open when her breathing stopped; I wondered if she would stay in her beautiful dream, whatever it was, forever.

I was spared no part of the process; my mother said a witch cannot make full use of a meal if she does not know it wholly. I asked her what use I was meant to make of food, other than eating it. She smiled as she picked up a bucket of my sister’s blood and replaced it with an empty one. “You’ll see,” she said in a sing-song voice.

In all things, she taught me, there is power. A witch does not create something out of nothing; she simply perceives what is already there, and uses it. My mother showed me how to reach with my senses and discern that which is invisible to the eye. The soul of a thing, one might call it: all the intangible aspects that make anything what it truly is, rather than what it appears to be. My sister was sweet and dull, but she had a kindness to her that we rarely had the chance to see. She was a natural provider, who would have loved to take care of people who needed her, and she had a knack for creating. What she really would have loved, I think, was baking. Of course, she never had the opportunity to try.

It was this collection of powers I consumed from her: benevolence, creativity, magnanimity. While her physical body sustained me and our mother, her spiritual self continued to live in me, and grow with me. I felt my own capabilities double, power tingling at my fingertips. I sensed the world around me and all the possibilities contained in every piece of it, all the marvels I could create. I could not sleep at night, not due to hunger pangs, but due to the endless whirling of my fevered mind, constantly alive with thoughts of spells I could cast and potions I could conjure. And all this with the dead, famined world! What wonders could I work in times of plenty?

My elder brother was next. In life, he never had the chance to grow strong in body, but he was strong in spirit. Restless and unyielding, full of courage and resilience. With him, I felt a fire in me, blazing hot and prickling my skin from the inside. I wondered what he would have done with this precious power: wasted it in the army, fighting someone else’s battles, or seeking selfish adventure in far-off places? I used his power to survive. I like to think it was a worthy cause.

My younger brother was last. Small, guileless, the most delicious of all. He hardly had time to grow foul with the bitterness in which life soaks us. His power was curiosity, and eagerness to learn. Oh, how we loved to learn, he and I: the names of the few plants my mother’s garden could provide us, the beautiful words of a powerful spell, the process of grinding and boiling and conjuring. My mother’s lessons in witchcraft found in me the most willing student, fuelled by the ceaseless wonder I absorbed from my brother.

I remember the day I first felt water on the wind. Small, barely perceptible particles flecked my face, and the cold impact was invigorating. The dull, dusty skies grew dark with clouds like bruises, black and blue. In the distance, the rumbling thunder sounded like a low hum. When the first fat raindrops fell on my bare arms, I screamed, half in delight and half in utter shock. My mother laughed, and we danced in the rain together, feeling the water, full of vitality, seep down into the thirsty earth and unlock the magic buried deep beneath the surface.

It was as if the world had awoken from an enchanted sleep. For the first time, I saw trees burst into bloom with bright green leaves that smelled of the sun, and delicate pink flowers that floated on the ebullient breeze. The soil’s hard, dusty brown became a rich, dark dirt that squished between my fingers and toes. I watched our herbs grow tall and thick with stalks, and our vegetables grow swollen and juicy.

During the famine, no one had looked much beyond their own fences. It was a time of each family focusing on their own, hardly looking further ahead than what they would eat for their next meal. Once the anxious quest for survival consumed less of our waking time, the community began to knit itself together again. There was time for visiting, for observing, for gossip.

The disappearance of my father and all of my siblings did not go unnoticed. At first, there was shock and pity. The neighbours murmured sympathetically about what unthinkable tragedy must have befallen us, that we lost so many. But the sympathy did not last long. They noticed that my mother and I were healthy. They noticed we did not wear black. To this, my mother retorted that my father had left us in debt, and we had not yet recovered enough from the lean times of the famine to be spending money on new clothes. To their first observation, however, she had no response. She merely shrugged, telling them that we were simply lucky. Luck did not exist in those times. Luck was a superstition, a force of something beyond the mortal world. It was dangerous to be lucky.

There were quiet whispers hidden behind closed shutters. Then, our neighbours grew bolder. They talked outside our garden gate while my mother smiled serenely and pretended not to notice.

“Murderer,” they spat at her. “Witch.”

The day they came for her, we were sitting in the garden together. She was quizzing me on the names of the herbs, pointing and asking me each one as we harvested them. Thyme, for courage. Tarragon, for perseverance. Rosemary, for remembrance. Their sweet scents mixed together on the wind, cold and damp with the promise of rain.

I smelled fire as they approached. I knew it before I looked up. My mother knew it, too.

The mob pressed against the gate. Amongst the crowd, several held torches and yelled my mother’s name, and “witch.” The man at the front of the pack held a dirty shovel in one hand and a wool blanket, bundled up like a sack in the other.

Without a word, the man released one side of the blanket, letting the pile of bones inside fall to the ground on our side of the gate. Each bone was snapped, sucked dry of marrow. If they looked closely, they might have seen our teeth marks. Perhaps they did.

My mother reached for my hand and squeezed it, once, before they kicked through the gate and grabbed her hair. I remember her face as they dragged her away. She did not scream or cry; she would not give them the satisfaction. She looked peaceful as an angel, her glowing red hair bright as a sacred flame atop her head, as she mouthed the word, “Go.”

The herbs fell from my lap as I scrambled to my feet. I ran through the house, letting the front door bang behind me as I made for the back. I did not stop to take anything. I often wonder what happened to all my mother’s stores, her dried herbs and precious tinctures, but there is little use in wondering. At the time, I thought of nothing but running. I ran over the field where our vegetables grew, past the holes in the corner where they had found the buried bones. I ran past the boundaries of the town, my bare feet slapping on the slippery stone of the bridge over the brackish river. I ran into the forest, dark and tall and welcoming, full of vibrant spirits teeming with life and magic all their own.

I reached a clearing inside the forest and stopped. Panting and out of breath, I sat on the ground, curling my fingers in the long, soft grass beneath me. The sound of the rain hitting the canopy of leaves sounded like little fingers tapping on a table. Grey light filtered through the trees, and every glimpse of the world outside the forest seemed to be of a world in the clouds, misty and opaque.

Closing my eyes, I reached out to explore the forest with the senses inside me. My sister found sweet nuts and berries, plump and ripe. My elder brother discovered a pure white bird, its long, curling tail feathers tangling with pine needles as it sat on a branch and whistled a cheery tune. My younger brother wondered at the thick tree trunks, the odd little mushrooms, the babbling brook, the smells of animals he had never seen and could not imagine.

On the wind, I smelled smoke, singed hair, and ash. The acrid taste stuck in my throat. I could almost feel the flames at my feet, licking higher and higher, blistering my skin and blackening my bones. Flecks of dust floated before my eyes and I hesitated to touch them, afraid of what truth I would be unable to forget if I did.

I felt the hunger of four people, a hunger I had not felt since before my father’s disappearance. The ache in my stomach called to mind a time so long ago it felt like a different life, back when all we knew was lack and misery. I looked back on the little girl I had been, so weak and frail and powerless, and I did not recognise her. Now, I was a witch, and a witch far more powerful than my teacher had been. I possessed all that she had taught me, and more that I had learned myself. And I would never be hungry again.

My sister’s skill for providing brought me everything I needed to survive. I found, or I conjured, every tool I required. The forest was abundant — almost unbelievably so. Stray stalks of wheat, the odd beet and carrot sticking up between the bushes and trees: it was as if magic had brought everything I could ask for to the forest, and let it grow while it waited for me to arrive. I assembled my kitchen, a witch’s laboratory, and arranged the seeds of creation at my fingertips. Then, I learned to bake.

The spicy-sweet smell that rose from my little oven filled me with satisfaction before I even tried a bite. I ate the first loaf before it cooled; it burned my tongue, but the hot, crumbly texture was so sublime, I could not resist it. I gulped it all down, and though my stomach’s ache subsided, I immediately made another. Why not? I was not limited by meagre stores of resources, as we had been my whole life during the famine.

I let the second one cool, and noticed how firm it was, how sturdy. When I realised what I could do with it, I laughed, loud and clear and strong in the empty forest. The ringing sound echoed, and I heard the rustle of birds’ wings as they flew away from the unexpected noise.

It was a ridiculous idea, I admit, but I grew up in a famine, and it was the only house I had ever dreamed of. A house made of food. What a silly extravagance! What an impossible wish. But I could grant my own impossible wishes now.

So, I built the house of gingerbread in the forest. I had such abundance that I could spare food for my walls, and still never starve. It made me laugh to look at it every day, and it kept my spirits high.

The passing of time was of no consequence to me. I did not keep track of how many days or years had gone. Time belonged to the outside world, to the world that killed my mother and scorned me. They did not want me, and I did not want them. We were perfectly content to leave each other in peace.

For the time being, at least. They would forget me for a while, I knew, just as our neighbours had left us alone during the famine. But we were always one tragedy away from confrontation, and my certainty in my power wavered when I thought of standing against the outside world. Once again, I imagined walls around me, to keep prying eyes away.

It was another famine that ended our unspoken truce. Though the forest was just as plentiful as ever and my stores remained unchanged, I could smell it on the wind: that familiar dry, dusty breeze that wheezed hunger and death in its weak meandering. The world inched its way toward me. I could say there was nothing I could do to stop them, but that would be a lie. I had my walls, I knew warding spells, I knew how to keep them out of my forest and away from my house. It was my younger brother, I think, that stopped me from doing this. He was curious. He wanted to see what would happen when we were found.

I heard the chopping of trees in the distance. I did not investigate, but I felt the forest change. As more common people populated my enchanted world, the magic went out of it, bit by bit. The abundance that had enticed people to move into the forest quickly dwindled, for they did not have the magic to replenish it as I did. I was not about to do it for them. They did not want me or my magic. They feared it and shunned me. I assumed it was only a matter of time until they all left or died, and I was perfectly content to wait it out.

They were not content to wait for their inevitable demise, however. They started to search the forest, and in doing so, found me. Rather, they found my house. They did not bother with me until it was too late.

Greedy, grubby hands snatched at my walls, clutched at my roof tiles, pulled up my candy garden and smashed my biscuit doors. They stuffed their mouths with my home, destroying my creation as they had destroyed the life I had in the village with my mother. I had run here to get away from them, but they sought me out, devouring everything I had built. Perhaps I should have known I could not hide from them forever.

But I was no longer the little fledgling witch that had run away from them. Now, I could bite back.

I did not need to eat them, of course. I was not starving. But as I had learned from my mother, there is food that feeds the physical body, and there is food that feeds the witch. They provided me not with mere sustenance, but with spiritual life. I devoured from them their courage, their cleverness, their strength. I came to enjoy hearing the little teeth gnawing at my windows and walls, knowing that a far greater meal awaited me shortly thereafter.

Still, their presence was a sign of a greater problem, and I did not wilfully ignore this. I knew the more the world knew of me, the more danger I was in from them. The taste of smoke from my mother’s funeral pyre rose in my throat, reminding me at every meal what end awaited me should the outside world close their grasping hands around me.

I tried to believe that every person who had come provided me with more resistance against their world — that the more power I gleaned from them, the more I could stand against those who opposed me. They did give me what they had, to be sure; but they were nothing special, and I knew it. There was no latent magical aptitude in any of them, nothing to bolster my own power. They had strength, though nothing to compare with my elder brother’s. They had curiosity, though far outmatched by my younger brother’s. They had wisdom, though none rivalled my mother’s.

On the bright side, once I dealt with the intruders, there were fewer outsiders overall. It was the only weapon I had against them, really: decreasing their numbers. I destroyed the common folk over and over, yet I could not forget how tenuous my victory was. They only had to destroy me once.

At first, I noticed nothing different about the two children who came to my house. I heard two sets of footsteps approach, the squelch of my walls between their fingers, the snap of my shutters in their teeth. I crept to the side of the window, careful not to let myself be seen as I peered out at them. They were the first children I had seen in the forest, and my curiosity was piqued. Who would allow children to wander alone in the woods, and why?

The girl stood on her toes, reaching for the window. I stepped back and watched her hand break through the sugar glass. Shards fell at my feet, barely making a sound as they fell to the gingerbread floor. She wrenched the rest of the pane from its place in the wall and disappeared from sight. The sugar cracked as she gnawed on it.

I sweetened my voice with all my sister’s gentleness. “Nibble, nibble, where’s the mouse? Who’s that nibbling at my house?” I called through the broken window.

The children gasped in fright. I stifled a bitter laugh. Children of common people were no different from adults: selfish and stupid. What did they think, that a house made of gingerbread in the forest had created itself just for them? That it was theirs for the devouring, that it was not even worth checking to see if someone lived inside?

In sing-song unison, the children sweetly replied, “The wind so mild, the heavenly child.”

Heavenly. The laughter became harder to stifle. Well, if they wanted to play at divinity, I could show them the power of worlds beyond their own.

I smoothed my dress and walked to the door, opening it with my sister’s kind smile plastered on my face. “Why, dear little children, how in the world did you get here?”

They did not answer. They were thin and pale, barefoot and dressed in dirty old rags. The boy’s hands were behind his back, no doubt holding a piece of my house, but the little girl had frozen in place, a shard of my window in her hands as she gaped up at me.

I sensed in them something I had not seen for a long time: something uncommon. Despite their actions, they had a wisdom beyond their years, a cleverness and quick wit. They were not merely resilient; the ability to survive in the face of adversity is a passive one. In them, there was a fierce and active will to live. The girl, in particular, buzzed with latent energy, alive with an internal fire.

Where had these children come from, and who were they? Perhaps I did not need to be so concerned about the outside world seeking me out to destroy me like they did my mother, if they were so dull as to let their most promising and powerful members wander into my clutches. It was no use speculating on what had brought these children to me; the fact was that they were in my world now, and it was time for me to act on what was within my power to do.

“Come inside,” I said, stepping back to usher them into the house. “You can stay with me.”

I conjured a feast on the table and their little eyes widened in wonder. Bread, soft and warm as if fresh from the oven, filled the house with the scent of salt and yeast. Thin pancakes, piled high on a platter, with butter and sugar, crisp sliced apples, nuts and little red berries bursting with bright, sour juice. Hot porridge with cinnamon, and cold lemonade, tart and sweet. Cakes of every size and colour, decorated with delicate birds and impossible flowers. A fresh loaf of my incomparable gingerbread, which I placed before them with a wink. “In case you haven’t already had your fill.”

The boy at least had the decency to flush with embarrassment. “We didn’t know anyone lived here.”

I waved a hand dismissively. “Never you mind, dearies. Eat as much of this as you please.”

Eagerly, the boy grabbed handfuls of everything and stuffed his face with all the grace of a pig. The girl ate more daintily, and her eyes travelled around the room as she nibbled. The boy was of little interest beyond what I already knew, but the girl…

I watched her as she surveyed my house and my belongings. The shelves full of herbs, bottled tinctures and salves, potions and elixirs, my cauldron bubbling at a quiet simmer in the corner: she took in everything she saw with an unbothered curiosity. She showed neither terror nor shock, but simply interest. I wondered if this was what my mother felt like as she watched me survey her own magical stores.

Eventually, they had eaten their fill and grew drowsy. I conjured a little room for them with two beds, made with fresh, white sheets. As we walked to the room together, the boy curled one tiny hand around one of my fingers, rubbing his eye with his other hand. I could feel the bone beneath his thin skin. It would take time before they were worth eating. Of course, it was not the physical meal that was my chief concern, but they could be such an indulgence, and was that not worth a little time?

The next day, I set more food before them. The boy stuffed himself greedily, while his sister again ate only her fill. While they ate, I worked on repairing the damage they had done to my house. I mixed the solution for the windowpane the girl had broken, sugar and henbane, ice water and hemlock root. I felt her eyes on me as I stirred the boiling concoction.

“What are you making?” the girl asked.

I turned over my shoulder to see her sitting sideways in her chair, chewing a piece of gingerbread as she watched. “I am fixing the windowpane.”

The girl flushed. “Oh.” Quickly recovering, she pointed at the jars I had taken off the shelf. “What are those for?”

I tapped each jar in turn. “Ice water, fresh and crystal clear, for true sight through the glass it makes. Sugar, to melt and thicken the glass. Henbane, for protection and abundance.”

“What about that one?” she asked, pointing to the bottled hemlock.

I smiled, and did not answer.

Days went by, and the children grew rosy and plump with health. The girl followed me around the kitchen, asking questions and offering to help. I could almost see the magic flowing from her fingertips, in little whirls of stardust and flower petals. I thought of my mother, seeing magic in me, and wondered if this girl’s mother had passed on her gifts to her daughter, too. But then, what witch would have been foolish enough to let this treasure go?

The boy certainly had no magic in him. He had his powers, of course, his wit and cleverness. But it was the girl who had real potential. It was the girl who had magic. I saw clearly, as my mother had done before me, that the boy’s purpose was to feed the girl, and it was my purpose to teach the girl what I knew.

“Darling,” I said to her one day. “Why don’t you go fetch some water?”

She nodded and hopped down from the stool next to the oven. “Shall my brother go with me?”

“No,” I replied. “I have another job for him.”

While she was away, I grabbed the boy’s meaty little arm and locked him in the shed outside. It was simple enough to cast a muffling spell on him, quieting his shrill, irritating shrieks. When the girl returned, I lit a fire in the oven, and set the water to boil.

I took her hand and sat next to her at the table while we waited. The excitement bubbling within me made my lips quiver; I dreamed of the magic she and I could work together, of how her magical education would increase both our knowledge and skill.

She looked at me with mild confusion. “Are you alright?”

“Yes, my dear,” I half-whispered. “I have something very wonderful to share with you.”

Her eyes lit up and she smiled, her flushed cheeks shining like tiny apples.

“My darling,” I said, hearing my mother’s voice echoing my own, “you have magic in you.”

The girl frowned and tilted her head. “What do you mean?”

“You are like me. My mother saw magic in me when I was your age,” I murmured, brushing a lock of hair off her forehead, “and I see it in you. I can teach you to use it.”

“Do...do you mean...you’re a witch?”

I sighed, exasperated with the dullness the world had inflicted upon her. “Well, of course. What did you think all of this was?”

The girl swallowed. She tried to pull her hand back from mine, but I gripped it hard.

“You can be a witch, too, my dear,” I told her, excitedly. My words raced from my mouth. “I can teach you. Don’t you want to learn to do all of this, what you’ve seen me do? Don’t you want to do magic?”

She did not meet my eyes, and I could hear the gears of her mind turning. “I suppose...I could take care of my brother and myself, if I could do magic.”

“Ah.” I leaned back in my chair. “Your brother. You needn’t worry about him.”

“What do you mean?”

“I had a brother, once. Two, in fact. And a sister. Do you know where they are now?”

She shook her head.

I patted my chest. “They are within me. I had my own power, of course, but theirs made me stronger. Your brother will make us stronger, too.”

“What do you mean?” she repeated.

The rapid bubbling of the boiling water caught my attention. “It’s time.” I picked up my knife from the counter. “Don’t worry,” I assured her. “He will not suffer. It will be quick.”

The girl looked up at me in horror. A flicker of doubt jumped in my mind; had I misjudged her? Was I so desperate for more power that I had imagined her magic?

She moved so rapidly I did not realise what she was doing until it was done. The iron oven door screamed as she opened it. The sound was still ringing in my ears as I felt her hands on me, stronger than they should have been, pulling and shoving. Before I knew it, I was surrounded with fire.

I felt a howling scream inside me, but would not let it out. I remembered my mother’s serene face as she was dragged to her own pyre. They can have our lives, but not our pain. I felt my skin blister and break, and the prickling heat of the blaze engulfed me in silent agony. Through the flames, I saw the girl’s terrified eyes meet mine and I held her gaze as long as I could, until they melted into the walls of orange that filled my mouth and lungs with hellish heat. Darkness crept in, roaring at the edges of my consciousness, and the last thing I saw was the trail of my mother’s ashes, dancing on the breeze.