Fairytales for Troubled Times: Hellboy

First posted September 2021.

There is a (possibly apocryphal) story of Greta Garbo watching the 1946 Jean Cocteau film, La Belle et la Bête, and standing up at the end after the prince’s transformation, yelling, “Give me back my beast!” Whether or not that actually happened, the sentiment is well-supported. After all, the whole point of Beauty and the Beast is that the Beauty falls in love with the Beast as, you know, a beast. To have him change immediately afterward is at best a shock, and certainly there’s more than one Beauty who found that a disappointment.

Yes, we’re talking about Beauty and the Beast for yet another del Toro film. I really could have called this series “Variations on Beauty and the Beast in the Films of Guillermo del Toro” but that’s a much less snappy title. Besides, I do have other things to mention! I promise!

Thus far in this series, I’ve only looked at del Toro’s original works, and it’s interesting to look at those versus his adapted stories. My only knowledge of the Hellboy comics comes from this movie and its sequel (note: I’m not looking for a primer for the comics, please don’t trouble yourself with educating me in this sphere), but I think it’s a safe assumption that the things del Toro emphasises in his adaptation are things that drew him to the source material in the first place, or things he loves that he felt complemented the story.

As presented in this film, Hellboy is obviously a story well within del Toro’s wheelhouse. Once again, we return to a Beauty and the Beast thematic turn hinged on the ‘what makes a beast and what makes a man’ discussion, but as del Toro states in the commentary, he envisions this particular treatment of the classic story as a “Beast and the Beast” version.

This film’s telling of Beauty and the Beast picks up nearly two-thirds into the story, at the part where Beauty has left the Beast (per Abe, “Liz left us, Red”). In written versions of the fairytale, Beauty leaves to visit her family, and assure them that she’s happy and safe with the Beast. In Hellboy, Liz has left the Bureau to try to learn to control her supernatural power and live like a ‘normal’ person.

We first see Hellboy and Liz interact in what del Toro refers to in the commentary as a fairytale garden. Trees wrapped in plastic and lit from inside the covering isn’t a tie to any specific fairytale, per se, but the enchanted garden aspect definitely brings us back to Beauty and the Beast, invoking the title characters walking and talking amongst rows of magically ever-blooming roses.

Where Beauty finds her safety with the Beast, Liz seeks it away from Hellboy. However, safety isn’t really possible for Liz in Hellboy — the danger Liz is running from is the uncontrollability of her own power, so no matter where she goes, the danger goes with her. We see this in action when Rasputin forces a nightmare on her that triggers her power to send the hospital up in flames. This incident sends her back to the Bureau; after all, if she’s a danger anywhere, she might as well go back to the castle.

The return in the fairytale is a moment of horror. The Beast warned that if she delayed in returning, he would die. Of course, she did, and she returns to find him deathly ill (or, indeed, dead, in some versions). Luckily, she is able to bring him back to life, either by a declaration of love, a kiss, or even just her presence.

Liz’s return in Hellboy is a moment of triumph. I’m not talking about her literal moment of return, when she comes back to the Bureau, but her moment of return to self, or her acceptance of power. Hellboy is in a dangerous fight, and Liz, who previously repressed and ran from her power, finally takes charge of it and accepts herself as one of the “freaks” in order to save him. Conveniently, it’s previously been established that the demons’ one weakness is, in fact, her superpower: fire. In del Toro’s “Beast and the Beast” moment, Liz becomes the Beast in order to save her Beast.

And pointedly, there is no transformation; Hellboy is still Hellboy. There is, as he says, “nothing I can do about this,” gesturing to his face. But of course, Liz loves him anyway. Garbo, eat your heart out.

Imagery in a comic book movie is unavoidably influenced by the source material. In the commentary, Mike Mignola and del Toro discuss many specific images that translated identically from the page to the screen, much of which is dripping with mythological references — and indeed, there could be a whole separate essay on mythology and theology both narratively and aesthetically in this film. But looking specifically from a fairytale angle, there are several instances of fairytale imagery even in this comic adaptation.

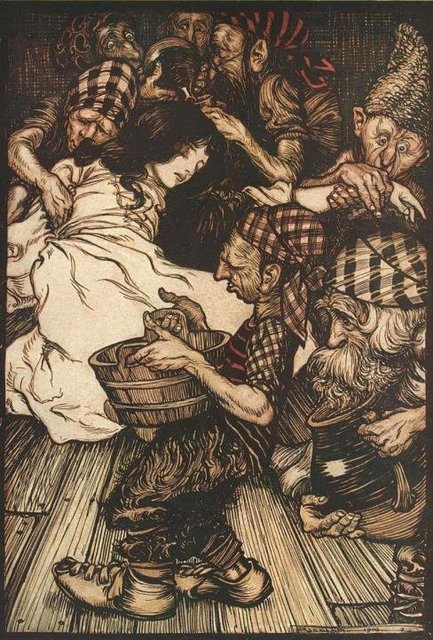

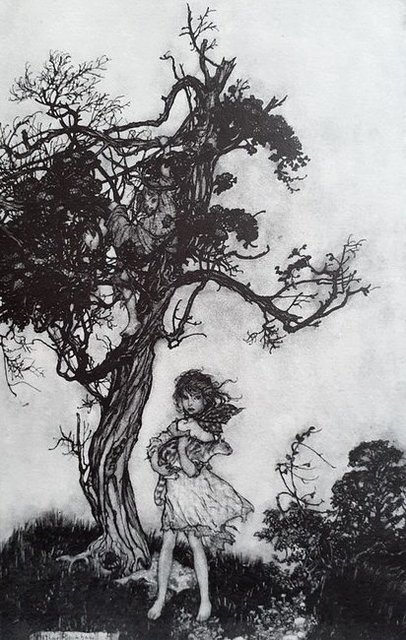

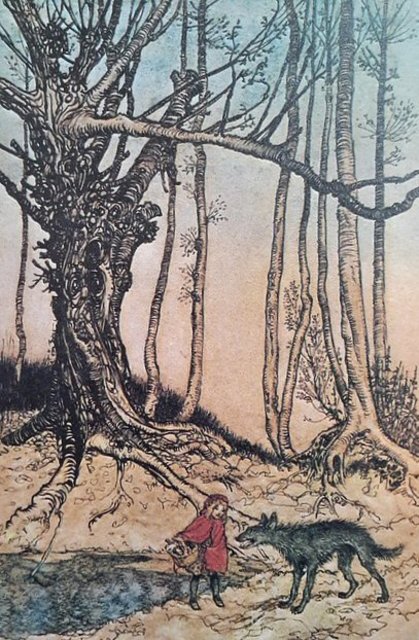

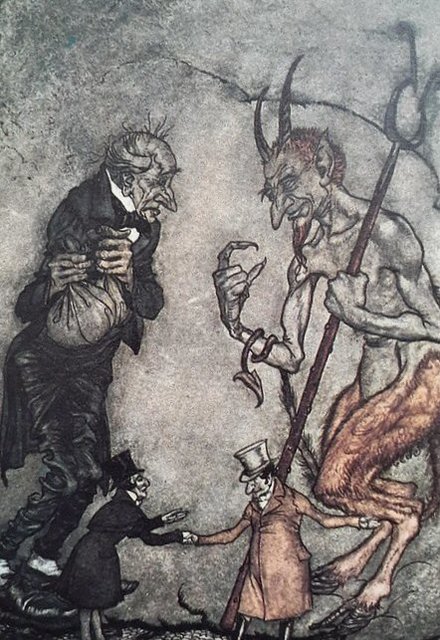

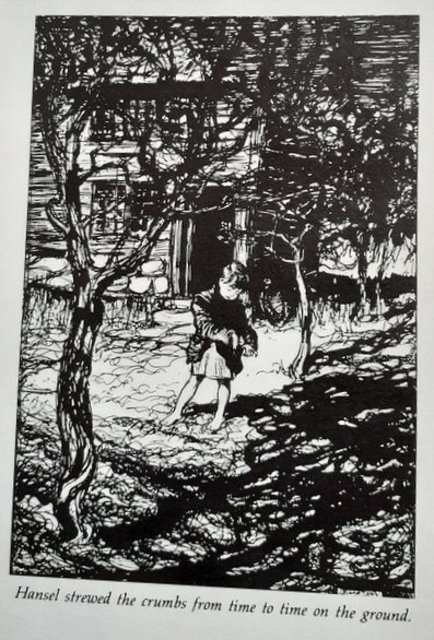

In the film’s opening, del Toro mentions in the commentary the design of the landscape. He points out a specific tree created by the design department that they called “the Rackham tree” during production, a reference to the famous fairytale illustrator Arthur Rackham. Rackham’s trees are indeed very distinctive and prominent in his work:

Rackham is one of my favourite fairytale illustrators, and I’m not surprised he’s one of del Toro’s, as well. His illustrations are known for their darker edge, which lends itself very well to Hellboy. Shadows drench the screen, obscuring Hellboy during his introduction both as a baby and as an adult, and Rasputin emerges from blood and darkness.

Several tales illustrated by Rackham make brief appearances in Hellboy. Tales like Tom Thumb, Thumbelina, and The Hazelnut Child feature childless parents wishing for a child and being sent a strange, tiny child through unusual magical means. Hellboy’s arrival and adoption by Professor Bloom certainly fit this story type.

Rasputin invokes Hansel and Gretel when talking to Bloom in the professor’s office. He mentions the clues he’s left to lead Bloom through his research: “Bread crumbs in a trail, like in a fable.” What’s interesting to delve into with regard to Hellboy and Hansel and Gretel is the role of the father. Hellboy considers Bloom his father as much as Bloom considers Hellboy his son.

The father’s role in Hansel and Gretel is complicated; he is responsible, of course, for abandoning his children in the forest hoping they’ll die so he won’t have to worry about the cost of feeding them any more, but the tale also takes pains to show the mother or stepmother (depending on the variant) goading the unwilling father into taking this course of action. Hellboy’s position is as unwanted as the children’s, and, weirdly, just as potentially lethal. He isn’t quite imprisoned, but he’s definitely kept sequestered, only allowed outside to hunt monsters for the FBI. When he breaks out of his own accord and for his own reasons, his father grows exasperated and insists more urgently on his confinement. Both fathers put their children in danger, though what they say they really want is to keep them safe.

The very brief mention in the commentary of Snow White, purely as imagery associated with the sleeping Liz, brings up a kind of thesis point in this essay series. Even when del Toro’s films aren’t explicitly narratively tied to fairytales, the themes which he uses imagery and narrative to represent are often themes associated with or explored in the fairytales he invokes. That his work is steeped in fairytales even when it isn’t directly engaging with them is essentially the point behind this series. Guillermo del Toro obviously knows a lot about fairytales and loves them, and that’s evident all over his work if you just know where to look for it. I find it enriches the experience for me — like he includes in-jokes for other fairytale nerds, giving you hints to larger story themes and character arcs. Using a simple symbol to invoke an entire story gives you a deeper understanding of what’s going on in the film you’re watching.